|

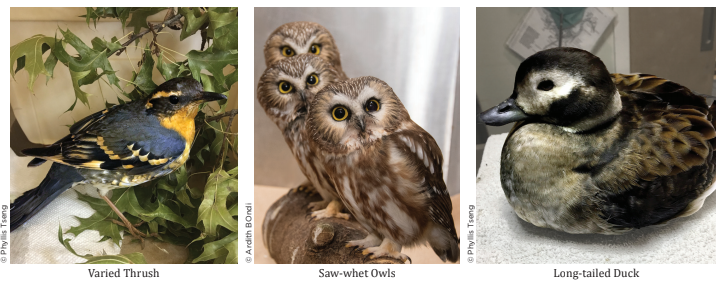

Dear Friend of Wildlife, If a New Yorker finds an injured wild bird, there’s one place in the city dedicated to helping wildlife, the Wild Bird Fund. Since 2012, New York’s only wildlife rehabilitation center has cared for over 29,000 birds and other animals. From the humble and underappreciated pigeon to the majestic peregrine falcon, WBF cares for the sick and injured brought in by thousands of compassionate New Yorkers. WBF is open 365 days a year to care for over 355 bird species that live in or migrate through the city. Besides wildlife, it is the only safe refuge for domestic fowl in need. Abandoned backyard hens, escaped runner ducks, and lost peacocks all find their way through our door. But we couldn’t do it without the thousands of hours donated by our loyal volunteers, nor without your generous contributions. Please take this opportunity to support the city’s sick, injured, and orphaned wildlife by making a donation to the Wild Bird Fund of $1,000, $500, $250, $100, $50, or a gift amount that is meaningful to you. Your gift enables WBF to continue to provide the excellent care and rehabilitation of birds like Coral, the American kestrel and Abby, the long-eared owl, whose stories are featured below.

Coral Walker-Cinco was with a group of high school students pulling invasive plants from Gantry Plaza State Park in Long Island City when she noticed something fall from a tree. She went over to see what it was, and lying on the ground was an American kestrel, our smallest falcon. The kestrel struggled mightily to get back up into the tree but kept falling back down. Soon she gave up and closed her eyes, exhausted. Coral made air holes in a shoe box, and battled traffic into Manhattan for an hour before she reached WBF. Tests showed that the kestrel, now named Coral, had substantial lead poisoning and had lost her sight. After three weeks of medicine, the lead was gone but Coral still could not see, which meant she could never go free to the wild. Coral’s only chance was to become an education animal. For weeks, the prognosis was not good. The bird was despondent, wouldn’t eat, tucked her head to sleep through the day, and did not enjoy human contact. But Coral didn’t give up, and neither did we. After many days coaxing life back into the handicapped bird, Coral now eats entirely on her own. She steps up to leave her cage and sits happily on a hand or shoulder. Acclimating a bird to human contact is called “manning” in falconry, and Coral now seeks human company. She flies freely, knows how to avoid hitting the ceiling and walls, and flutters down softly where we can pick her up for another flight.

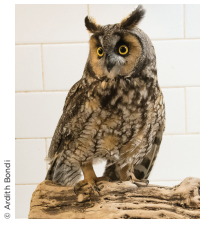

Long-eared owls are rare visitors to the city. Abby was the first ever brought to WBF. She suffered a concussion and a swollen eye from colliding with the glass building. Anti-inflammatories and antibiotic eye drops helped, but it was Barry and Paul’s intervention that really saved her from dying of hypothermia due to that night’s single digits. Abby was feisty throughout her rehabilitation, puffing up to twice her size to look more intimidating. She recovered in three days, and on New Year’s Day she was ready for release. In a twilight lit by a supermoon, Abby was set free in front of a small crowd of WBF members. But then a Cooper’s hawk swooped in by the extra light of the full moon to attack. The aerial battle was short but tense. As darkness waxed, Abby gained the advantage and the Cooper’s hawk took off. That’s what we aspire to: wild birds being in the wild sky. We couldn’t have saved Abby or Coral without the financial support of people like you. Your gift will help end suffering, heal wounds, and nurse orphans back to life, as well as educate New Yorkers, especially their children, about wild animals and their place in our city. Your gift is appreciated. Your investment in wildlife makes a difference. The Wild Bird Fund cannot survive without your support. Your donation is also fully tax deductible and good for your soul. Thank you! Rita McMahon P.S.: Please donate today as generously as you can!

|

Abby, the Long-eared Owl

Abby, the Long-eared Owl